The annual High Blaze exercise took place in the north of Italy this summer. During the exercise, helicopters of the Royal Netherlands Air Force Defense Helicopter Command (DHC) practice flying in the mountains. The rugged landscapes, changeable weather conditions and difficult landing sites provide challenging conditions to operate in.

160 people, two Eurocopter AS532 Cougar helicopters, and three Boeing CH-47D Chinook helicopters were deployed to Aviano Air Base to take part in the training. Initially, there would be five more Apache helicopters but due to an abnormality on the surface of a tail rotor blade, the Apache participation was canceled. Around 50 vehicles and 50 containers drove to Aviano from Gilze-Rijen Air Base in The Netherlands.

GOALS OF THE EXERCISE

We spoke to detachment commander Major Boudewijn Stevens, who bears the end responsibility for the troops, helicopters and achievement of the training objectives. He explains what those objectives are:

“The primary goal is to train new pilots and loadmasters in mountain flying. The pilots and loadmasters must become familiar with the environment and the challenges of flying at higher altitudes.

There are also three secondary goals set. First the training of previously qualified pilots and loadmasters, because mountain flying skills are perishable. Therefore, as many operational pilots and loadmasters as possible participate in the exercise to maintain those specific skills.

The other secondary goal is the deployment and redeployment of the composite squadron. We operate here as one squadron that is composed of at least six different squadrons. In that way we are able to deploy almost 200 persons, dozens of trucks, containers and multiple helicopters via air and ground from Gilze-Rijen Air Base and set up our operating base somewhere else and perform our flight operations.

The last secondary exercise goal concerns the communication aspect. In a challenging mountainous environment we check our equipment and improve our knowledge by setting up different types of connections.”

SELF-SUPPORTING

The composite squadron is designed in such a way that it is as self-supporting as possible. While relying on a modular concept the composite squadron can be tailored to specific needs.. “For this exercise we brought our own fire brigade as well as petroleum specialists to fuel the helicopters” Major Stevens clarifies. “But we also rely on Host Nation Support provided by the US Air Force and Italian Air Force based on Aviano.”

PREPARATIONS

“Moving this many troops and helicopters may require an extensive preparation. Therefore we rely on standard operating procedures. To verify that the described procedures are still valid and to maintain proficiency in case that a scenario requires us to deploy somewhere else, the logistic deployment is one of the secondary training goals.”

Upon arrival, there are no theory days and flying starts as soon as possible. The pilots love this exercise. We spoke to Captain Thijs, who is a Chinook pilot. Although it’s not his first time in the mountains, he describes the usefulness of the training: ”The majority of the flight hours we make are in the Netherlands, which is as flat as a pancake. There are no hills, let alone mountains, to train on. That makes mountain flying difficult, because as you can imagine, it is very easy to put down the helicopter on terrain that is flat. Everywhere you look you are able to land.”

TYPES OF LANDINGS

The challenge for the pilots is to find landing spots in the mountains, so that is what they train the most. There are a variety of landing types in the mountains. Captain Thijs sums them up: ”We have the pinnacle landing, which is an open part on a mountain where you can land the helicopter with all four wheels. We are looking for a spot that is as flat as possible.

Then there is the ridge-line landing, which is very nice to do. This incorporates a landing on a ridge of the mountain with only the rear wheels on the ridge to simulate that we have a place where it is impossible for us to stand with the entire helicopter but it is urgent to pick up or drop off people.

There is also the valley approach, so if, for example, you have a spot at the bottom of a valley with a mountain pass above it, you can imagine, we don’t fly there casually, but there is a whole procedure to drop into a valley or climb to reach such a place.

And then we have what we call the bowl landing, a lower point in the mountains. For example a crater like you see at a volcano where you have to fly a certain pattern to land in. These are all things that we really cannot train in the Netherlands, and we are definitely not very good at it because we just do not do it often.”

AREAS – BUILD-UP

The Dolomite mountains in northern Italy are the perfect place to train these kinds of landings, due to the different types of terrain, and the large area. Captain Thijs shows the area on a map: “The area runs from Lake Garda to the Austrian border. There is also a build-up in the areas. Some areas are somewhat lower or flatter, which is a bit easier to train. Because we are training different people at the same time. We give people an initial mountain flight training, but there are also guys like me who are working on the annual exercise program that is about maintaining your mountain flying level or getting better. We can land anywhere in the entire area. New spots are added every time, we are searching and we can land randomly if we find a good place there. What we do take into account is that there are people living there, even at that height. We try to stay away from all areas where houses are located.”

INDIVIDUAL TRAINING

There is an individual training exposure in this exercise for every pilot and loadmaster, but the crew concept is also very important in the course. A trainee from the loadmasters and a new pilot might fly together for some flights, or fly with an experienced pilot or loadmaster to accentuate the individual aspect more. Furthermore, the High Blaze exercise is focused more on the technical flight aspect instead of the tactical aspect concerning ground support in air raids and assaults.

HEIGHTS – POWER

When asking about the challenges in mountain flying, Captain Thijs answers managing power is very different. “In the Netherlands or in Germany when we train, we usually fly low level with a maximum height of around 2.000 feet. Here we sometimes fly up to 10.000 feet. At 10.000 feet the air is thinner. You feel a difference in the controls. You have to make bigger motions to be able to steer the helicopter.

But the biggest change is mainly the power. The performance of the helicopter simply decreases. Usually we are limited in the amount of power that we can use as a load on the transmissions, in the mountains we are more limited by the engines because they reach a maximum temperature we do not want to exceed, so we can get less power out of the engine. This means that we can take fewer things with us, but we also have to change the way we approach. What we often do when flying in the mountains is taking into account the fact that an engine may quit. If your power is suddenly reduced by half due to an engine failure, you can imagine that it has a considerable impact. What we do is adjust our approach in such a way that we have an escape. We make sure the escape allows us to build up sufficient speed to improve the performance of the helicopter. At a higher speed you often need less power and the engine system works more efficiently with its air.”

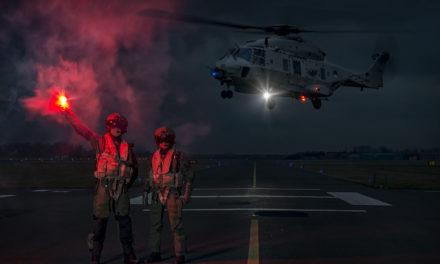

NIGHT FLYING

For Captain Thijs, this is not the first High Blaze exercise, but it is the first time training these procedures and landings at night. “That makes it even more complicated. In the Netherlands, when we fly at night with night vision goggles, we often have residual light from cities. What the goggles need is a little bit of light to enhance, so residual light from a city, or a freeway, it all helps. But in the mountains there are places with no artificial or natural light, that is really imposing. The infrared searchlight is used to light such areas.”

MISSION OVERVIEW

A typical High Blaze sortie starts with a map study, coordination with other crews concerning the intended training areas and establish a communication plan with frequencies to communicate with each other and with ground personnel. After this, there will be a crew brief and then the crew grabs their flying gear and go to the helicopters. When the pre-flight checks are performed, the helicopters start-up and take-off heading towards the mountains. The flight to the designated area’s takes 20 to 30 minutes. When the often unpredictable weather is confirmed and a recce pass is executed, they start the first landing. “We tell the crew for example: I would like to land on a ridge-line. Good luck.” says Captain Thijs. “Then we search for a suitable ridge-line. If we have identified the landing location from a higher altitude, we drop down to determine if the location, wind and altitude are suitable and to decide what approach strategy we will use. We calculate the power we have and the single engine safe speed if an engine fails. Then we practice once without landing. We validate again whether the location is good or not, and then we set up for landing. This way we practice different types of landings.”

CONCLUSION

Captain Thijs clearly enjoys the exercise: “This is the cherry on the cake for us all. We are in Italy, so the weather is very nice.” Major Stevens is also happy, for different reasons. “The results of the exercise were great. We were able to perform 95 percent of the flights that we had planned. That is an exceedingly high realization percentage. That says something about the deployability of the helicopters, but more importantly that the maintenance support is carried out in an effective and efficient manner. To realize that as a detachment is something we are very proud of.”

The training goals were all achieved, leaving the Major very satisfied. Being a pilot himself, it was a fresh challenge for him as well to be the detachment commander: “Usually I am just at the end of the process of producing flight hours: I step into the aircraft and go fly a mission. It takes a lot of people to make that possible. As a detachment commander you are experiencing that up close and see all the components of this well-oiled machine. Especially if you are abroad as a self-supporting squadron where you have to stand on your own two feet. In my opinion it is important to realize that, whether you are the sergeant who maintains helicopters or the corporal of the ground-based equipment, you are all an indispensable link in a machine to ensure that we produce those flying hours. They sometimes say, if one of those links is missing no one will fly and that’s very true. We can look back on a very successful exercise.”

Exercise High Blaze 2019